By the WSLC Labor Immigration Committee

Versión en Español aquí.

Download a printable PDF version of this toolkit.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

AFL-CIO 2019 Immigration Statement

- Introduction

- Racial and Immigrant Justice

- Supporting Immigrant Justice In Our Unions and In Our Workplace

- Community and Coalition Building

- Sample Flyers

- Appendices

- Contact Us

- Feedback

AFL-CIO 2019 IMMIGRATION STATEMENT

As our nation continues to roil with issues stemming from poverty, oppression and racism, appeals to division and hatred inevitably make us all weaker and poorer. The escalating attack on immigrant and refugee families in our country is an affront to labor’s values and a clear threat to the freedoms we all hold dear.

Family is the reason we go to work every day. America’s unions categorically reject policies that tear families apart. Yet what we see in our country today is a dramatic and deliberate increase in the casualties caused by our broken immigration system.

The AFL-CIO opposes immigration enforcement tactics like raids that breed fear in our communities and chill the exercise of basic workplace rights.

The AFL-CIO opposes immigration enforcement tactics like raids that breed fear in our communities and chill the exercise of basic workplace rights.

We demand government agencies that serve the greater good and are accountable both to their workforces and the public.

We reject family and child detention, the “zero tolerance” policy at the border and any limits on due process for vulnerable populations.

We insist that the way to raise wages and standards is by empowering workers and creating pathways to citizenship for all those whose labor helps our country to prosper.

As we denounce the proposed raids, America’s unions are preparing to respond. Across the country, we will continue to fight for all working people and stand strong with members of our communities and our unions in the face of these attacks.

Working people want real solutions, not callous and cruel campaign stunts.

The labor movement remains committed to the ongoing struggle to address the root causes of forced migration and build an immigration system that lifts people up and ensures that we are all able to live and work with dignity, regardless of where we were born.

We know that real security can only be achieved through humane approaches, and we will continue to demand justice for long-term members of our communities, our workforce, and our unions, as well as for those who newly seek refuge in our country.

We will prevail by rejecting the politics of division and building a strong, inclusive and democratic movement for justice for all working families.

INTRODUCTION

About This Toolkit

This toolkit is designed to provide documented and undocumented workers, worker advocates and union leaders with the resources and support they need to create a just and fair future for immigrants in the United States. We understand the fight for immigrant justice and the fight for worker justice to be one in the same, and that all union members deserve the right to equal protection from their union. The vision for this toolkit is to empower leaders in the labor movement to use their existing structures of leverage as both shields for their immigrant workers and platforms for justice. This toolkit was created by the Labor Immigration standing committee of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO (WSLC) in response to a resolution passed in 2019 (Resolution #14). It reflects the true collaborative spirit only a coalition with such diversity can bring.

This toolkit is designed to provide documented and undocumented workers, worker advocates and union leaders with the resources and support they need to create a just and fair future for immigrants in the United States. We understand the fight for immigrant justice and the fight for worker justice to be one in the same, and that all union members deserve the right to equal protection from their union. The vision for this toolkit is to empower leaders in the labor movement to use their existing structures of leverage as both shields for their immigrant workers and platforms for justice. This toolkit was created by the Labor Immigration standing committee of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO (WSLC) in response to a resolution passed in 2019 (Resolution #14). It reflects the true collaborative spirit only a coalition with such diversity can bring.

This has been drafted with the understanding that each union or worker organization has a different capacity and awareness. We acknowledge that funding and questions regarding support for the implementation and accountability of some of the recommendations in the toolkit are crucial to this process. Skepticism or opposition should not stop us or sway us from moving forward. There have been many initiatives that have begun with limited support but have grown to become hallmarks of the labor movement. It is critical to see a commitment to worker justice as equal to a commitment to immigrant justice and fight against any injustices in our workplaces.

How to Use This Toolkit

This Toolkit contains three primary sections:

- An introduction and overview to understand the current challenges immigrants face in the United States.

- A set of agreements and recommendations to ensure that a racial justice lens is used hand in hand with immigrant justice initiatives.

- A checklist of essential measures unions or worker organizations can take to support their immigrant workers. This includes, but is not limited to: Recommended Contract Language, An Outline for Language Access, and Resources for Raids and Audits.

This Toolkit is designed to be used as a reference guide for making actionable and sustainable changes that better the lives and working conditions of immigrant workers. The changes can come in a variety of forms from internal cultural shifts to formal resolutions. This Toolkit contains guidance for these important changes and reflects the ethos of the WSLC Labor-Immigration standing committee.

Introduction to Immigrant Justice

Many immigrant workers lack necessary protections to prevent and combat workplace abuse. The immigrant community is particularly vulnerable to abuse from employers who take advantage of their documentation status. The work of immigrant justice is to ensure that immigrants are treated fairly, equally, and with dignity. As long as there is differential and discriminatory treatment of workers, we believe that there can be no class unity.

Current Immigrant Experience in Washington State

- About one in seven Washington residents is an immigrant, while another one in seven residents is a native-born U.S. citizen with at least one immigrant parent.

- In 2018, 1.1 million immigrants (foreign-born individuals) comprised 15 percent of the population.

- Washington is home to 538,989 women, 500,147 men, and 65,714 children who were immigrants.

- The top countries of origin for immigrants are Mexico (23 percent of immigrants), India (8 percent), China (7 percent), the Philippines (6 percent), and Vietnam (6 percent).

- In 2018, 1.1 million people in Washington (15 percent of the state’s population) were native-born Americans who had at least one immigrant parent.

- An ICE report released on May 18, 2017, shows “during the first 100 days of this year, agents with ICE’s field office in Seattle arrested 1,070 people in Washington, Oregon, and Alaska — a 33 percent increase over the same time period last year” (KUOW).

- ICE also released a statement that deportations are up 40% nationwide. The Trump administration has instilled fear in already-vulnerable communities, as ICE hunts people in their homes and on the streets. Families are being broken apart, children are being left without parents to care for them, and our communities are missing valuable contributors

Source: The American Immigration Council

Detention Systems

The United States manages the largest immigration detention system in the world. American taxpayers spend over $2 billion each year to detain an average of 34,000 individuals daily—nearly half a million people annually—under a bed quota established in congressional appropriations.1 Individuals are held in a network of more than 200 detention facilities across the country. Roughly half of detained immigrants are held in state prisons and county jails, which contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the interior enforcement agency of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), to detain immigrants.2 The rest are held in dedicated immigration detention facilities run by ICE or contracted to for-profit private prison corporations, such as Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) or the GEO Group (GEO). Facilities often are punitive and remote, cutting immigrants off from their families, access to counsel and the opportunity for fair hearings. A true victory for the immigrant justice moment came in 2021, when after years of organizing and coalition support, House Bill 1090 was passed in Washington, ending government contracts with private detention systems. The Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, one of the largest such facilities in the country, will close its doors forever in 2025.

The United States manages the largest immigration detention system in the world. American taxpayers spend over $2 billion each year to detain an average of 34,000 individuals daily—nearly half a million people annually—under a bed quota established in congressional appropriations.1 Individuals are held in a network of more than 200 detention facilities across the country. Roughly half of detained immigrants are held in state prisons and county jails, which contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the interior enforcement agency of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), to detain immigrants.2 The rest are held in dedicated immigration detention facilities run by ICE or contracted to for-profit private prison corporations, such as Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) or the GEO Group (GEO). Facilities often are punitive and remote, cutting immigrants off from their families, access to counsel and the opportunity for fair hearings. A true victory for the immigrant justice moment came in 2021, when after years of organizing and coalition support, House Bill 1090 was passed in Washington, ending government contracts with private detention systems. The Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, one of the largest such facilities in the country, will close its doors forever in 2025.

- The National Immigrant Justice Center

- How the US Immigration System works

- Facts on Immigration powerpoint

RACIAL AND IMMIGRANT JUSTICE

Race and immigration in the United States have a deep interconnected history. As a labor movement, our ability to address comprehensive immigration reform in our membership relies on our skill to create authentic relationships with our immigrant members, understand their needs, and honor their lived experiences through our everyday actions as a union. To do this well, it becomes imperative to center racial equity within our immigrant justice work.

In 2020, the WSLC made two constitutional changes in the name of racial justice. (Learn more about the WSLC’s Race and Labor program.) These can be used as guiding lines to structure the ongoing fight for true equity in the workplace:

In 2020, the WSLC made two constitutional changes in the name of racial justice. (Learn more about the WSLC’s Race and Labor program.) These can be used as guiding lines to structure the ongoing fight for true equity in the workplace:

2.1 Purposes. The purposes of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO are… (l):”to fight to end structural and anti-Black racism as part of our work to build a wider movement that will fight for an economy that works for everyone—including supporting people who are joining together to raise wages and improve workplace standards, fix our broken immigration system, to advance women’s rights, LGBTQ equality, and to ensure that every community has clean air and water.”

6.11 Oath of office: “I, (name), hereby solemnly pledge my word of honor as a member of organized labor, that I will perform the duties of the office to which I have been elected, as provided for in the constitution, and that I will use my best efforts to forward the interests of this organization, all branches of the AFL-CIO, all workers’ rights, and to stand up against racism, sexism, homophobia, and all forms of oppression in our movement, in our workplaces, and in our community.”

More resources:

- Racial Equity Terms and Definitions Glossary (PDF)

- Racial Justice Analysis and the Four Types of Racism workshop

- SEIU’s Blind spot workshop + Powerpoint

- The Government Alliance on Race + Equity (GARE)’s Toolkit

- Hour lecture by Bill Fletcher on Race + Labor

- The Sum of Us, What Racism Costs Everyone by Heather McGhee

Agreements

The following is a list of principles to uphold at your union local or worker organization:

- Avoid making assumptions about other people.

- Be open to critical self-reflection. If an individual tells you that something you said was harmful to them, listen.

- Realize your privilege and be aware of potential power dynamics that might exist within a space.

- Understand that we are all in a place of learning. If you say something problematic – apologize, listen to the voices of others, and then learn and adjust your behavior.

- Share the space and give appreciation freely.

- Speak for yourself. Use “I” language; don’t speak for others and don’t share someone else’s stories or experiences.

- Notice your own biases/judgments.

- Prioritize transformational conversations as opposed to transactional.

- Create an atmosphere in which principled debate can unfold about the direction of organized labor and its relationship with race.

- Look critically at the structural inequalities of your local and organization in regard to race.

- Uphold the racial justice resolutions passed by the WSLC

Questions to Center for Facilitated Discussion

The questions below can be reserved for staff meetings or introduced in less formal settings with the goal of introducing sustained and critical conversations surrounding race and power in the workplace.

- How often do you think about your racial or ethnic identity?

- What can we do to work on our bias in our lives and in our unions?

- What aspect of your racial or ethnic identity makes you the proudest?

- In what ways does your race or ethnicity impact your personal life? Your professional life?

- How does racism weaken unions?

- How does racism inhibit workers’ ability to advocate for safer workplaces and communities?

- Have you ever experienced a situation where your racial or ethnic identity seemed to contribute to a problem or uncomfortable situation?

- Does racial or ethnic identity enter in your process of making important or daily decisions? If so, how?

- Have you ever witnessed someone being treated unfairly because of their racial or ethnic identity? If so, how did you respond? How did it make you feel?

SUPPORTING IMMIGRANT JUSTICE IN OUR UNIONS AND OUR WORKPLACE

The fight for immigrant justice and worker justice are not separate; without one, there is not the other. For generations, immigrants and refugees have been the backbone of our society but yet continue to face institutional and societal barriers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen the rampant inequities towards the immigrant community with the lack of personal protective equipment, unsafe working conditions, lack of affordable quality health care during a pandemic, and lack of access to social safety nets including unemployment insurance.

The fight for immigrant justice and worker justice are not separate; without one, there is not the other. For generations, immigrants and refugees have been the backbone of our society but yet continue to face institutional and societal barriers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen the rampant inequities towards the immigrant community with the lack of personal protective equipment, unsafe working conditions, lack of affordable quality health care during a pandemic, and lack of access to social safety nets including unemployment insurance.

As members of the labor movement, we must commit to breaking down barriers and fighting for immigration reform that protects and ensures the safety of all immigrants and refugees in this country not only in their workplace but also in the larger community. Workers are not defined by only their job title but who they are in their respective communities. Labor unions must integrate steps in our movement and contracts to reform a system that continues to disenfranchise and oppress those who have sacrificed so much and continue to be the foundation of our country and workforce.

Union Checklist

This checklist is to guide labor unions on how to continue advocating for immigrant justice and protecting their workforce. It is broken down by internal and external, what can be done within the labor unions itself and how the labor unions can advocate in the broader community.

Internal

□ Understand your membership including:

□ Track and document the demographic makeup

□ Track and document preferred written and spoken languages of your members

□ Survey immigrant members’ specific experiences and needs

□ Include contract language that:

□ Provides paid time off and protection of their job for immigration-related issues

□ Protect jobs and contract rights of all workers regardless of immigration status

□ Requires employers to provide communication verbally and written in the preferred language of the workers

□ Provides severance pay for visa-related termination (see Appendix C)

□ Commits employer to avoid voluntary enrollment in the flawed E-Verify system.

□ Mandating that employers not consent to ICE entering the premises without a warrant

□ Requiring employers to notify workers and their union immediately after ICE commences an audit

□ Provide your membership with:

□ Know Your Rights Training for encounters with ICE.

□ Information translated in languages that your membership needs.

□ Interpretation at member meetings, contract negotiations and events.

□ Easily accessible resources for members to know what is available to them if contacted by ICE, such as resource cards

□ Education about immigration reform

□ Access to one-on-one legal council for members who have immigration status concerns

□ Provide education for non-immigrant members on how to be in solidarity with immigrant workers.

□ Hardship Funds/Solidarity Funds for workers who can’t access government safety net programs (i.e. unemployment benefits) because of immigration status.

□ Scholarships to cover the cost of becoming a Legal Permanent Resident or new citizen.

□ Invest in immigrant members’ leadership by:

□ Creating a pathway for immigrant members to step into leadership positions, i.e. bargaining team members, committee leaders, local union officers and staff.

□ Formalize leadership development tracks for immigrant members, provide ongoing mentorship.

□ Encourage members to join constituency groups to support their leadership development

□ Connect members to WSLC constituency groups. APALA, LCLAA, CBTU, APRI, Pride at Work & CLUW

□ Provide membership support if an individual member is detained by ICE.

□ Develop a Rapid Response Plan for the union and all job sites with immigrant workers in preparation for immigration raids or audits.

□ Provide Rapid Response trainings for members and assign responsibility roles

Naturalization Legal Aid for Union Families

(Also available in Spanish, Chinese and Vietnamese.)

The Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO (WSLC) acknowledges that citizenship is fundamentally a labor issue, and helping working people access citizenship strengthens our labor movement. The WSLC offers its Naturalization Legal Services program to union members and immediate family members of union members who have legal permanent residency in the United States and are interested in applying for U.S. citizenship. Citizenship offers protection to workers and helps workers feel empowered to assert their labor and civil rights. Obtaining citizenship is a major benefit to each worker and it opens up opportunities for workers that improve overall quality of life for themselves and their families.

The WSLC offers appointments for immigration consultations and naturalization applications (N-400). Services are available both virtually via Zoom and in-person at Nuestra Casa, located at 906 E. Edison Avenue in the city of Sunnyside. Service hours are varying and may depend on the availability of parties involved. Union members interested in learning more about the WSLC Naturalization Legal Services or who wish request an appointment are encouraged to email Dulce Gutiérrez at DGutierrez@wslc.org or call 509-833-3096 and leave a voicemail.

Costs and fees:

Consultation fee = $10.00

Application Completion and Submission Service fee = $50.00

DHS Application fee = $725.00 (payable to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security)

COMMUNITY AND COALITION BUILDING

- Advocate for state and federal policies around immigration reform

- Host or partner with community organizations to provide Know Your Rights Training to the community

- Amplify and respect the voices of existing immigration advocacy groups

- Build relationships with existing immigration advocacy group

- Donate money and resources to existing immigration advocacy groups

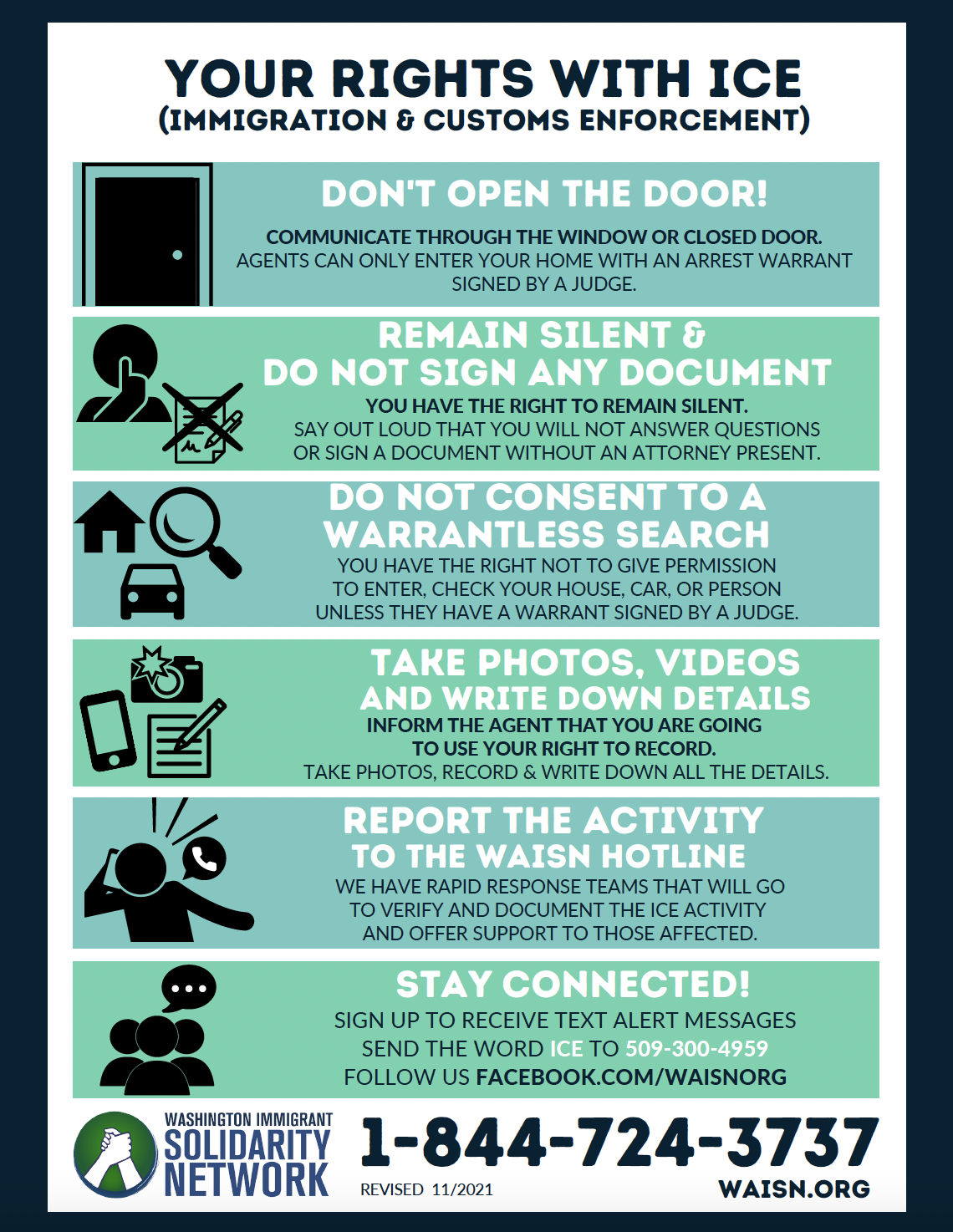

The Washington Immigration Solidarity Network (WAISN) is the largest immigrant-led coalition in the state of Washington. They are a network of immigrant and refugee-rights, faith and labor organizations and individuals distributed across the state dedicated to protecting, serving and strengthening immigration communities. Please visit their website for an extended list of resources.

The Washington Immigration Solidarity Network (WAISN) is the largest immigrant-led coalition in the state of Washington. They are a network of immigrant and refugee-rights, faith and labor organizations and individuals distributed across the state dedicated to protecting, serving and strengthening immigration communities. Please visit their website for an extended list of resources.

Resources for Raids and Audits

- The Washington Immigrant Solidarity (WAISN) Hotline: 1-844-724-3737

- AFL-CIO Toolkit for Organizers and Advocates on Workplace Raids and Audits

- Examples of Specific Contract Language Regarding Immigration Matters

- Legal Aid At work: Workplace Raids, Workers Rights

- Clinic Legal Rapid Response ToolKit

- Preparing for ICE Workplace Audits: An Organizing Approach, Video and 7 Steps Flyer

- ImmigrantDefenseProject.org

- The Washington Immigrant Solidarity Network (WAISN) accompaniment program

- Tools and resources to help protect and prepare youth and families in case of an immigration raid, AFT

Contract Language

In order to strengthen worker protections and clarify procedures, unions may bargain with employers over potential responses to irregularities in immigration status, and other related issues. In the event of an upcoming contract negotiation or labor management session, union representatives can push for the inclusion of immigration-related provisions in the collective bargaining agreement or relevant side agreements. The language that we use in our contracts can either be used to uplift more workers into higher paying positions and win further protections to all workers, no matter their ethnicity, education level, and immigration status, etc., or it can be used to perpetuate racist structures at work.

Please see Appendix C for extended examples of specific contract language.

Language Access

Language Access is providing communication services for those whose language is not the main language being used whether it be in verbal or written. It brings equity and clarity for those who are not proficient in the dominant language which in the United States is English. Recognizing the barriers and creating access for those who are Non Native English speakers, allows those to fully participate in their preferred and most comfortable language.

There are four types of access that can be provided:

- Translation — The rendering of source language content from one language into another language in written form.

- Interpretation — The rendering of a written, spoken or signed message from one language into another spoken or sign language.

- Consecutive Interpretation — The rendering of a speaker’s or signer’s message into another language when the speaker or signer pauses to allow interpreting.

- Simultaneous Interpretation — The rendering of a speaker’s or signer’s message into another language while the speaker or signer continues to speak or sign.

Best Practices: Working with Interpreters

Interpreters are professional workers.

- Hire (and pay) certified interpreters – If possible, hire union Interpreters.

- Include language justice point person in the logistics/planning phase of an event.

- Brief interpreters about the purpose and plan of the event.

- Include expectations and responsibilities for interpreters, and the resources (equipment, point person, preparation materials, meals, parking considerations, nametags, etc.) that will be required and/or available to them.

- Hold tech run-through with interpreters prior to the event.

- Share relevant content, vocabulary lists, one-pagers, videos, articles, slides and meeting agendas as early as possible or at least 48 hours in advance.

- Hire 2 interpreters per language pair for simultaneous interpretation.

- Interpreters are bound by their code of ethics to be impartial, remain neutral and keep all information confidential.

- Remember that Interpreters have varying skill levels and specialties. Talk with them about your expectations before hiring them to make sure they have the qualifications you need.

- i.e. ability to interpret in both directions, subject matter expertise

- Respect work hours and break times, including meals, for interpreters!

Pathways to Language Justice

Basics-> Translation->Interpretation-> System/Structure

Basic

Local knows all of the main languages spoken by its members and about what percentage of each language makes up the base. You can also break it down by turf and sector of work.

Action Items:

- Member survey to voluntarily collect language data or update it

- Check in with the organizing team to identify members where language is a barrier

Translation

Local translates written communications into the main languages spoken by the membership (membership cards, contracts, website, etc.)

Action Items:

- Identify translation services that best fit your Local’s needs

- Internally coordinate translation project (materials, budget, team, glossary, etc.)

Interpretation

Local provides professional simultaneous interpretation at all union meetings and events. Said meetings and events are not English dominated. Tele-town halls are available in all languages of the membership. English speakers willingly use simultaneous interpretation equipment at union events to understand what is said when English is not being spoken. There is simultaneous interpretation available at bargaining sessions so members can participate regardless of their English language skills.

Action Items:

- Identify Interpretation vendor that best fits your Local (Hire Union Interpreters when available)

- Develop an interpretation plan (budget, scale, team, etc)

System/Structure

- Local has a dedicated budget for professional translation and interpretation services.

- Local owns its own simultaneous interpretation gear.

- There is a pathway to leadership for Limited English Proficient (LEP) member leaders, demonstrated by the existence of LEP delegates, stewards, elected leaders, etc.

- There are organizers and other union staff that speak the languages of the membership.

- Continuous commitment to improve language justice through Intentional recruitment practices that views language diversity as added value vs. barrier to engagement.

- Strong shared understanding of language justice with racial justice and equity in the union.

To hire an interpreter please refer to INTERPRETERS UNITED, Washington Federation of State Employees, AFSCME Council 28.

To hire an interpreter please refer to INTERPRETERS UNITED, Washington Federation of State Employees, AFSCME Council 28.

Please see Appendix D for examples of Work orders drafted by INTERPRETERS UNITED.

From Language Access to Language Justice

At its 2021 Convention, the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO hosted the following workshop covering success stories and best practices for increasing participation and building leadership within unions using Language Justice. It features Dulce Gutiérrez of the WSLC, Milena Calderari-Waldron of Interpreters United 1671 WFSE/AFSCME; Diana Salazar of SEIU 775; Alex Chuang of the Washington Immigrant Solidarity Network; Amy Leong of the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance; and Emilie Slater of the WA Labor Education & Research Center.

SAMPLE FLYERS

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Resources and Quick Links

National Resources:

- AFL-CIO toolkit — Form to request a copy

- AFL-CIO Know Your Rights Materials for Immigrant Workers

- AFL-CIO KYR card — English & Español

- New York Lawyers for the Public Interest Nonprofit ICE guide

- NILC KYR sheet — English

https://www.nilc.org/get-involved/community-education-resources/know-your-right/ - National Day Laborers Organizing Network KYR worksheet — English – Español – عربى(Arabic)

- NDLON KYR in public sheet — English – Español

- We Have Rights

- Immigration Preparedness toolkit for Immigrants (Spanish Version)

Washington State and Local Resources:

- NWIRP KYR flyer — English – Español

- WAISN KYR Flyer — English – Español

- WAISN ICE workplace response sheet — English

- WAISN Keep Washington Working sheet — English & Español

- NWIRP guide for detainees — English – Español

- Colectiva Legal legal aid contact information — English – Español

- Fair Fight Bond Fund — Website

- WAISN Hotline — 1-844-724-3737 (for various inquiries – Reporting ICE/CBP activity, report an individual or group detention, obtain referral info/assistance for someone who has been detained, access KYR information, access services such as the Fair Fight Bond Fund)

- Casa Latina — KYR (they have/create their own programs and resources, don’t need to refer to NDLON)

- American Imigration Lawyers Association

- Find an Immigration Lawyer

- WSLC Naturalization Legal Services

Appendix B: Glossary of Key Terms

A-Number — A unique seven-, eight- or nine-digit number assigned to a noncitizen by the Department of Homeland Security.

Asylum — A form of relief those who can prove a well-founded fear of or past persecution because of race, religion, nationality, political opinions, or membership in a particular social group if returned to his/her country of origin and he/she is not statutorily barred from such relief.

Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) — The highest administrative body within the Department of Justice that interprets and applies immigration law. The BIA hears appeals of decisions made by Immigration Judges (IJs). These decisions are binding unless overturned by the Attorney General or a federal circuit court.

Customs and Border Protection (CPB) — A law enforcement agency under the DHS tasked with policing the border and preventing people from entering the country without documentation. Has jurisdiction within 100 miles of any U.S. national border (North, South, and Coastal).

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) — An American immigration policy that allows certain undocumented immigrants who entered the country before their 16th birthday and before June 2007 to receive a renewable two-year work permit and exemption from deportation.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) — Department of the U.S. federal government. DHS is responsible for preventing terrorism, managing the border, and enforcing immigration laws. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) are agencies of DHS.

Green Card/Permanent Resident Card — A green card is a document which demonstrates that a person is a lawful permanent resident, allowing a non-citizen to live and work in the United States indefinitely. A green card/lawful permanent residence can be revoked if a person does not maintain their permanent residence in the United States, travels outside the country for too long, or breaks certain laws.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) — A law enforcement agency which exists under the DHS, primarily concerned with detention and deportation of undocumented immigrats.

I-9 Audit — A procedure in which ICE requires an employer to supply the I-9 records of all employees to ensure that they have legal status and are legally permitted to work. Can result in employer fine or employee termination if proper documents are not provided. Employers may also self-initiate one of these audits, sometimes as a way to retaliate or intimidate workers or unions.

I-94 Form — The Arrival and Departure Record is the I-94, in either paper or electronic format, issued by a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer to foreign visitors entering the United States. As of April 30, 2013, most Arrival and/or Departure Records are created electronically upon arrival.

I-94 Number/Admission Number — An 11-digit number found on Form I-94 or Form I-94A Arrival-Departure Record.

Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) — Any person not a citizen of the United States who is residing in the U.S. with permanent lawful status as an immigrant. Also referred to as “Permanent Resident Alien,” “Resident Alien Permit Holder,” and “Green Card Holder.”

Language Justice — The right to speak the language that you are most comfortable with. To be able to participate fully and to lead full lives regardless of what language a person speaks.

Naturalization — The process by which U.S. citizenship is conferred upon a lawful permanent resident after he or she fulfills the requirements established by Congress in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). The general requirements for administrative naturalization include: a period of continuous residence and physical presence in the United States; an ability to read, write, and speak English; a knowledge and understanding of U.S. history and government; good moral character; attachment to the principles of the U.S. Constitution; and a favorable disposition toward the United States.

NACARA — The Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act. Signed into law in 1997, NACARA provides various forms of immigration benefits and relief from deportation to certain Nicaraguans, Cubans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, nationals of former Soviet bloc countries and their dependents.

Raid — When officers of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) enter a place where they think undocumented immigrants might be, with the intention of detaining or deporting them.

Refugee — Any person who is outside his or her country of nationality who is unable or unwilling to return to that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution. Persecution or the fear thereof must be based on the person’s race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. Refugees are subject to ceilings by geographic area set annually by the President in consultation with Congress and are eligible to adjust to lawful permanent resident status after one year of continuous presence in the United States.

Repatriate — To return to one’s home country. Repatriation may be voluntary or involuntary. Voluntary repatriation is when a person chooses to return to the home country. Involuntary repatriation is when a person is forced to return to the home country against their will.

Resettlement — Moving a refugee from the country where they first asked for asylum to a different country. People waiting to be resettled are often kept in camps until a place is found in another country.

T-Visa — In 2000, Congress passed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (VTVPA). The VTVPA created a special nonimmigrant classification designated as the T-visa for victims of trafficking who are brought into the United States.

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) — A program for people from certain countries with very serious problems, like war or natural disasters. People with TPS can get a work permit and can stay in the U.S. temporarily. TPS is not a path to a green card or citizenship.

Temporary Work Visas — Work visas allow foreign nationals with specialized skills and/or knowledge to work in the United States. Prior to sponsoring a foreign national for certain types of temporary work visas, an employer must apply for and receive labor certification from the Department of Labor as well as be granted a petition from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Common temporary work visas include:

- H-1B visas for specialty (professional) workers

- H-2A visas for temporary or seasonal agricultural workers

- H-2B visas for non-agricultural temporary labor workers

- L-1 visas for executive assistants or

- D-1 program from crewmembers

USCIS — U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services is one of the new bureaus under the Department of Homeland Security, which replaced the INS in 2003. The USCIS is responsible for the administration of immigration and naturalization adjudication functions and establishing immigration services policies and priorities.

U Visa — The “U visa” protects immigrants who are crime victims by making it safer for them to report a crime or help law enforcement. A person who is the victim of domestic violence or trafficking, but who doesn’t qualify for VAWA or a T visa, can sometimes qualify for a U visa. Qualified applicants can get a work permit and stay in the U.S. They may be able to help other family members get a U visa, too.

Visa — A U.S. visa allows the bearer to apply for entry to the U.S. in a certain classification (e.g. student (F), visitor (B), temporary worker (H)). A visa does not guarantee the bearer the right to enter the United States.

Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) — VAWA protects family members of abusive U.S. citizens and green card holders by allowing them to apply for a green card without the help of their abusive family member. It is not just for women.

Citation: Stand With Immigrants, NWIRP, Freedom For Immigrants

Appendix C: Model Contract Language

AFL Immigrant Contract Language

AFL-CIO — Examples of Specific Contract Language Regarding Immigration

Introductory Contract Language

- The employer will not allow any Immigration officers to enter the workplace without a valid warrant signed by a federal judge or magistrate.

- The employer will immediately notify the union if the Immigration authorities contact the employer for any purpose so that the union can take steps to inform its members about their legal rights or to help them obtain legal assistance.

- The employer will allow lawyers or community advocates brought by the union to interview employees in as private a setting as possible in the workplace. The union might also have a legal plan, which provides workers with immigration attorneys.

- The employer agrees not to reveal the names, addresses, or immigration status of any employees to Immigration, unless required by law.

- The employer will not participate in any computer verification of employees immigration or work authorization status.

Immigration Reform and Control Act 1986

ARTICLE 20 CHANGE OF STATUS/IMMIGRATION

20.01 New Legislation. The Union and Employer will negotiate over issues related to the immigration status of employees under the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 or any current or future federal, state, or local immigration laws or other government rules or policies related to immigrants which impact bargaining unit employees.

20.02 Rights under this Agreement. Non-probationary employees covered by this Agreement shall not suffer any adverse action, including a loss of seniority, compensation or benefits, due to any changes in the employee’s name or Social Security number, provided that the new Social Security number is valid and the employee is authorized to work in the United States.

In the event that a non-probationary employee has a problem with their right to work in the United States, the Employer shall notify the Union in writing and, upon the Union’s request, agrees to meet with the Union to discuss the nature of the problem to see if a resolution can be reached. Whenever possible, this meeting shall take place before any action by the Employer is taken. The Union and the Employer have an interest in avoiding the necessity of terminating trained employees due to the employee losing their authorization to work in the United States.

The Employer shall not discipline, discharge, or discriminate against any employee because of national origin or immigration status, or because the employee is subject to immigration or deportation proceedings, except as required to comply with the law. An employee subject to immigration or deportation proceedings shall not be discharged solely because of pending immigration or deportation proceedings, so long as the employee is authorized to work in the United States.

D. Reverification

The Hotel shall not require or demand proof of citizenship or immigration status, except as required by 8 USC § 1324a or as otherwise required to do so in order to comply with the law. No employee employed continuously since November 6, 1986 or whose circumstances constitute “continuing employment” as defined in 8 CFR § 274a.2(b)(1)(viii) shall be required to provide such proof.

Employment Authorizations Expiration

The Hotel will provide an employee with at least sixty (60) days’ notice that the documents provided by the employee demonstrating work authorization are scheduled to expire and that the employee will need to re-verify their I-9 documentation and provide valid evidence of continued work authorization. Such notice will be provided to an employee through an electronic message to the employee’s account in the Employer’s human resource system. If the human resource system is unavailable, the Employer may provide notice to the employee at the time clock, by mailing a notice to the employee’s address on file, and/or by direct communication from the employee’s manager or human resources office.

Detention Proceedings Protocol

If the Employer is notified that an employee has been detained or incarcerated as a result of pending immigration or deportation proceedings, the Employer will place the employee on unpaid leave of absence for a period of twelve (12) months. If the employee is released and provides appropriate work authorization documentation within the twelve (12) month period, the employee will be returned to work without loss of seniority to his/her former job classification, displacing the least senior employee in that job classification.

Employees on leave of absence under this

Section 37.07(a) shall not accrue vacation or other benefits during the leave of absence.

20.03 Reinstatement. In the event that a non-probationary employee is not authorized to work in the United States, and their employment is terminated for this reason, the Employer agrees to immediately reinstate the employee to their former position, without loss of prior seniority, however, seniority, vacation or other benefits do not continue to accrue during the period of absence, upon the employee providing proper work authorization within twelve (12) months from the date of termination; and to the employee’s prior shift and station if the employee produces proper work authorization within ninety (90) days of the date of termination. If the employee produces proper work authorization between ninety-one (91) days and twelve (12) months from the date of termination, the employee would return without loss of prior seniority, to his or her former classification displacing the least senior employee in that job classification.

If the employee needs additional time, the Employer will rehire the employee into the next available opening in the employee’s former classification, as a new hire without seniority upon the employee providing proper work authorization within a maximum of twelve (12) additional months. The parties agree that such employees would be subject to a probationary period in this event.

If an employee obtains appropriate work authorization within five (5) years after losing work authorization status solely as a result of changes in DACA, DAPA or TPS status, the employee must provide documentation of work authorization and return to work within six (6) months after obtaining it or forfeit the leave provided in this subsection. The reinstated employee will displace the least senior employee in the employee’s former job classification until the next scheduled bid when they may utilize their former frozen seniority in that classification. An employee will not accrue vacation or other benefits based upon particular Plan policies during such absence.

The Employer will furnish to any non-probationary employee terminated because they are not authorized to work in the United States, a personalized letter stating the employee’s rights and obligations under this Section.

6. The Union and the Employer have an interest in avoiding the necessity of terminating trained employees due to the employee losing their authorization to work in the United States. In order to assist employees in a timely manner to take advantage of the prepaid legal services plan and /or other assistance provided by the Union regarding immigration matters, the Employer agrees to notify the Union of employment authorizations that are going to expire at least one hundred and twenty (120) days in advance of expiration. The Employer may satisfy this requirement by forwarding the Union copies of such employment authorization forms as soon they are received by the Employer.

Labor Notes

The Employer shall provide to the employee written notification when it contends that her work authorization documents or I-9 Form are deficient, or that the employee must reverify her work authorization, specifying: (a) the specific document or documents that are deemed to be deficient and why the document or documents are deemed deficient; (b) what steps the worker must take to correct the matter; (c) the employee’s right to have a union representative present during the verification or reverification process and; (d) any rights which the worker may have in connection with the verification or reverification process under this Agreement. The notice must be provided to the Union no less than 14 days before it is sent to the employee so that the Union may comment on the communication.

Upon request, the Employer agrees to meet and discuss with the Union the implementation of a particular verification or reverification process.

The employee shall have the right to choose which work authorization documents to present to the Employer during the verification or reverification process.

Workplace Immigration Enforcement

20.04 Compliance with Government Agency Requirements.

A. The Employer shall permit inspection of forms I-9 by the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”), or any other legally authorized government agency, only after a minimum of a three (3) day written notice. Such forms shall be maintained in a file separate from other human resources files and the Employer shall not retain in any of its files copies of the identity and work authorization documents presented by the employee at the time a form I-9 is completed.

C. Workplace Immigration Enforcement. The Employer shall:

- Notify the Union by facsimile or electronic mail within twenty-four (24) hours of receipt of a search and/or arrest warrant, an administrative warrant or subpoena from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), unless it is legally prohibited from doing so.

- Require DHS to present a search and/or arrest warrant, administrative warrant, subpoena or other legal process prior to conducting official business in the workplace, unless the Employer is otherwise required by law to admit such persons and/or emergency circumstances exist.

- Permit DHS to inspect I-9 forms, or documents other than the I-9 forms, only if and when compelled to do so by a valid written notice, arrest, search and/or administrative warrant, subpoena or other legal process, or as otherwise required by law.

(f) Notification of Immigration-Related Audits and Detentions

The employer shall notify the Union as soon as it has knowledge of an immigration audit, and upon request, provide the Union copies of any documents concerning the work authorization of any employee.

The employer shall notify the Union as soon as it has knowledge of any employees detained for immigration-related reasons and provide the Union the name, contact information, and detention location of any detained employee.

Note: In the past, we have experienced ICE raids at some of our work sites. The most critical assistance we can provide our members who are detained is to link them with an attorney as soon as possible. In order to do this, we need to have the most up-to-date information about an employee, since our records aren’t always accurate.

Contractor Transition

The Employer shall not request information or documents from employees or applicants for employment as to their immigration status, except as required by law. In the event of a change in management of the Hotel, the Employer shall transfer all forms I-9 to the new employer, pursuant to 8 C.F.R. Sec 274a.2(b)(1)(viii)(A)(7), unless otherwise agreed by the parties.

(g) Contractor Transition

An employer who takes over the account of another signatory employer must hire the incumbent employees and may not require them to complete I-9 Forms or be verified through E-verify unless required by law. An employer who loses an account to another signatory employer shall provide the successor with copies of the Form I-9 file for each bargaining unit member employed at the account.

The immigration law, regulations and USCIS I-9 Handbook provides that an employee is not considered a new hire where she was employed by one member of a multiemployer association, and then is hired by another member of the multiemployer association under the same collective bargaining agreement, and where the predecessor has provided copies of the I-9 Forms to the successor employer.

Notice of No-Match

B. In the event that the Employer receives notice, by correspondence or otherwise, from the Social Security Administration (“SSA”) indicating that some of the employee names and Social Security numbers that the Employer reported on the wage and tax statements for the previous tax year do not agree with the SSA’s records, the Employer agrees to the following:

- The Employer will provide a copy of the notice to the Union and to all employees on the notice;

- The Employer will not take any adverse action against any employee listed on the notice, including firing, laying off, suspending, retaliating, or discriminating against any such employee because the employee is listed on the notice;

- The Employer will not require that employees listed on the notice bring in a copy of their Social Security card for the employer’s review unless failure to do so would violate applicable law, complete a new form I-9 unless recertification is otherwise legally required due to pending document expiration, or provide a new or additional proof of work authorization or immigration status, provided that the Employer may advise employees, in writing only, that they should report any corrected information they may give to the SSA for proper tax reporting purposes;

- The Employer agrees not to contact the SSA or any other government agency after receiving notice of a no-match from the SSA unless failure to do so would violate applicable law;

Labor Notes

(b) SSA No-Match Letters or Other No-Matches

Except as required by law, neither an Social Security Administration “no-match” letter, nor a phone or computer verification of a no-match, shall constitute a basis for taking any adverse employment action against an employee, for requiring an employee to correct the no-match, or for re-verifying the employee’s work authorization. Upon receipt of a no-match letter, the Employer shall notify the employee and provide the employee and Union with a copy of the letter.

Note: An SSA “no-match” letter is issued by the SSA to employers and employees stating that the name and Social Security number of an employee submitted to SSA by the employer do not match. Employers may also use the SSA’s phone verification system to determine if the employee’s name and number match. The SSA’s purpose in ensuring the name and Social Security number match is to fully credit the worker with all of her earnings for determining Social Security benefits. SSA is not an immigration agency and at this time does not share no-match letters with ICE, the federal immigration agency. There are several reasons why a no-match could occur, e.g., a spelling error by the employer, discrepancies when employees have more than one last name, and it does not mean that an employee is not authorized to work in the U.S. Accordingly, we take the position that employees may not be fired for failing to fix the no-match.

Time Off Due to Work Authorization

20.05 Leaves of Absence. Upon request, employees shall be released for a total of five (5) unpaid working days in order to attend required immigration proceedings and any related proceedings for the employee only. The Hotel may require verification of such absence.

Labor Notes

The Employer shall grant up to four (4) months leave to the employee in order to correct any work authorization issue. Upon return from leave and remediation of the issue, the employee shall return to his or her former position, without loss of seniority. If the employee does not remedy the issue within four (4) months, the employee may be discharged for cause.

Note: This provision affords employees an opportunity to correct any immigration problems, e.g., an expired work visa, without losing their jobs or seniority. Note that a Social Security no-match is treated under subsection (b). This is because, under our view of current law, an employee is not required to fix a no-match. Hence, an employee faced with a no-match does not need the leave of absence, because there is no “problem” to be fixed.

20.06 English proficiency.

A. The Parties recognize that English is the language of the workplace and, while employees are expected to communicate in English when guests may be present. The Employer recognizes the right of employees to use the language of their choice, in a non-discriminatory manner, in conversations among themselves. Where it would not interfere with proper scheduling or Hotel operations, the Employer will cooperate with the Union and employees to permit employees to take literacy or English as a second language classes.

B. The Employer agrees that in meetings involving discipline, an employee who clearly needs language assistance, or who cannot fully understand the issues relevant to their discipline and requests language assistance, shall be provided translation assistance by the Employer. Any reasonable delay in interviewing or effectuating discipline as a result of such need shall not affect the timeliness of such grievance or discipline.

20.07 Citizenship.

The Employer encourages all employees to become active citizens, register to vote, and participate in voter education programs so that they can be informed voters. To celebrate employees who become U.S. citizens, the Employer shall excuse an employee from work on the day that an employee is sworn in as a U.S. citizen, and the employee will be paid the same amount as for one of the non-worked holidays listed in Article 16. Should this ceremony occur on one of the holidays listed in Article 16, an eligible employee will be paid the regular holiday pay plus one additional day’s pay at the employee’s regular rate of pay. Additionally, employees shall be allowed an unpaid day off to attend a citizenship ceremony for an immediate family member as defined in section 19.01.

20.08. The Union and the Hotel agree that this Article 20 shall not be interpreted to cause or require the Hotel to violate 8 USC § 1324a or any other applicable law.

Voluntary Participation of Verification Programs

5. The Employer shall not verify employees’ identities, immigration status,authorization to work in the United States or Social Security numbers through e-Verify, the SSA’s Verification Service, or any other method of checking such employee information with any government agency, unless required by law. This provision shall not prohibit the Employer from using these services for pre-employment screening;

(a) Work Authorization and Reverification

The employer shall not impose work authorization verification or reverification requirements greater than those required by law.

A worker going through the verification or reverification process shall be entitled to be represented by a Union representative or a personal attorney.

(d) Participation in E-verify and Similar Programs

The employer shall not participate in E-verify or other similar state or local program unless required by law. If participation is required by law, the Employer shall:

- Provide the Union a copy of its E-verify of other Memorandum of Agreement with the relevant government agency;

- Shall not use E-verify except for new hires, unless required by law. For purposes of federal E-verify, an employee shall not be considered a new hire as provided in 8 CFR § 274a.2(b)(1)(viii);

- Provide any affected employee 4 months leave to correct a final nonconfirmation or similar determination of lack of work authorization; and

- In the event an employee is terminated as a result of the lawful application of E-verify or similar program, the Employer shall pay the replacement employee the same wage rate as the terminated employee.

Note: E-verify is a federal program whereby Employers, utilizing ICE and SSA databases, verify the work authorization of its employees. For federal contractors, participation in E-verify is mandatory; for other employers, it’s voluntary. Some states have starting adopting similar programs.

Changes in Social Security Number or Name

(c) Change in Social Security Number or Name

Except as prohibited by law, when an employee presents evidence of a name or Social Security number change, or updated work authorization documents, the Employer shall modify its records to reflect such change and the employee’s seniority will not be affected. Such change shall not constitute a basis for adverse employment action, notwithstanding any information or documents provided at the time of hire. The employer may not question an employee about work authorization unless a union representative has been given the opportunity to be present.

Note: Employees change their name and Social Security number for a variety of reasons, e.g,. to reflect a name change due to marriage, or to reflect that they have corrected their work authorization status. In either case, the Union believes that employees should not be penalized for providing the employer corrected information. In the case of work authorization, employees should be encouraged. Accordingly, this provision is designed to make sure employers do not discipline workers who make these corrections. Otherwise employers may be able to fire workers, claiming they committed application fraud. An employer may object, claiming that continuing to employ such employees violates federal immigration law. However, it is our view that once an employee has corrected her status, there is no potential liability. To alleviate the employer’s concern, however, we can include the proviso “except as prohibited by law.”

(h) Legal Services Fund

Establish a fund that requires the employer to contribute on behalf of its employees that provides no or low-cost immigration legal services.

(i) Employment Records

Within 10 business days of the request, the employer shall provide employees with documents demonstrating the employees’ employment history with the employer and/or at the location.

Appendix D: Sample Work Orders

Example 1: Work order based on ASTM F2575-14 Standard Guide for Quality Assurance in Translation

Text in italics clarifies the questions briefly stated in the boxes in the left column.

| SPECIFICATIONS AGREEMENT | |||

| Payer | Full invoicing details | ||

| Work Order No. | |||

| Date of original request | |||

| Date of acceptance of estimate | |||

| Deadline | Depending on the difficulty of the text and the type of editing/formatting required, a reasonable time frame would be 2000 words per day for a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 8 or less, with at least two work days to complete each project in order to have time for input from a reviewer. This can be adjusted depending on the type of document and the needs of the client. | ||

| Requester | Name and contact information | ||

| Translator | Name and contact information | ||

| Reviewer | Name and contact information | ||

| Other team members | Name and contact information | ||

| Delivery method | Electronic, physical, regular mail, etc. | ||

| PRODUCT | |||

| Source

Text |

Word count | This can be run on Microsoft Word documents under Word Count | |

| Flesch–Kincaid grade level | Affects pricing | ||

| Flesch Reading Ease | Affects pricing | ||

| Locale and audience it was written for | |||

| Subject matter | Medical, legal, science, etc. | ||

| Type of document | Brochure and Poster | ||

| Format, including graphics | PDF Trifold.

Desktop Publishing. Needs to specify which software is being used for pricing purposes. The translator may not have access to it. Pricing is much lower if source and target text are delivered in a Word format. |

||

| Target

Text

|

Target audience locale and nationality | ||

| Purpose of translation | Publication, gisting, information for medical staff, etc. | ||

| How much localization is expected? | Are the units going to be converted to metric? Is it acceptable to change some text to communicate the same point in a more culturally relevant way? Changes of this type will be submitted to the requester for approval before being implemented. | ||

| Format for delivered text | Straight text? Formatted text? | ||

| Style guide to be used | |||

| Layout expectations | |||

|

Reference materials provided by requester |

Source and translated versions of similar texts. Previous translations or materials published in both the source and target languages on the topic will help the translator be consistent with previous work done by others. In some cases, the translator may suggest alternate terms. | ||

| PAYMENT | |||

| Rate per source text word | Standard are is generally based on a source text written and delivered in Word format below Flesch-Kincaid 8th grade level and a Flesch Reading Ease above 80. | ||

| Urgent delivery | Standard rate is generally based on one week from the date of the specifications agreement. | ||

| Terms of payment | |||

| Method of payment | |||

| Identification of translator in target document | |||

| Ancillary services fee | |||

Process of translation, based on ASTM Standard Guide for Quality Assurance in Translation F2575-06:

- Specifications agreement

- Terminology: develop glossary using client’s resources and ongoing translation process

- Translation

- Editing:

- Compare source text to target text for:

- completeness

- accuracy

- free from misinterpretations

- Referring only to target text:

- coherence

- readability

- Compare source text to target text for:

- Formatting and compilation

- Proofreading and verification:

- typographical errors

- spelling

- formatting

- Comparison with specifications

- Delivery

- Client review

Sample Price Sheet based on Flesch-Kincaid Readability Scores

| Reading Ease | School Level | Rate | Notes |

| 90.0–100.0 | 5th grade | Standard | Very easy to read. Easily understood by an average 11-year-old student. |

| 80.0–90.0 | 6th grade | Standard | Easy to read. Conversational English for consumers. |

| 70.0–80.0 | 7th grade | Standard | Fairly easy to read. |

| 60.0–70.0 | 8th & 9th grade | 5% surcharge* | Plain English. Easily understood by 13- to 15-year-old students. |

| 50.0–60.0 | 10th to 12th grade | 10% surcharge* | Fairly difficult to read. |

| 30.0–50.0 | college | 20% surcharge* | Difficult to read. Terminology research. |

| 0.0–30.0 | college graduate | 40% surcharge* | Very difficult to read. Best understood by university graduates. Specialized terminology research. |

*These surcharge percentages reflect the increase in the time it takes the translator to do the work.

2000 words per day or 300 words per hour are for a source text with a Flesch Reading Ease of above 80 and a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of below 8th Grade delivered to the translator in Word format.

Conversion from PDF into Word format for plain text: 10% surcharge

When there are charts and tables embedded in the document additional surcharges will be evaluated on a case by case basis.

Reviewer: 25% of rate per Word included in the translation price per word.

Example 2

Please provide this order with at least 4 days advanced notice

WORK ORDER

based on ASTM F2089-15 – Standard Practice for Language Interpretation

| Work Order number | |||||||

| Payer | invoicing details | ||||||

| LEP Client(s)/Patient(s) | name(s) or if confidentiality is at stake gender and number | ||||||

| Contact person | for further details | ||||||

| Date of original request | |||||||

| Date of acceptance & confirmation of estimate & work order | |||||||

| Contact person for further details | |||||||

| E

V E N T |

Date | ||||||

| Location | |||||||

| Start Time/End Time | |||||||

| Prep Time | Not always applicable but very important for certain event venues and settings. The interpreter should be expected 30 minutes before the interpreter begins. During this preparation time, the interpreter has the opportunity to check the equipment, speak to the presenters or those responsible for the session, and finish preparing for the session. This time is considered part of the assignment. | ||||||

| Area of Interpreting

(choose only one) |

· Business: interpreting performed in the course of business activities

· Community: interpreting (in community settings) for the purpose of outreach, information, community relations, and community services. · Conference: interpreting performed primarily in the simultaneous mode for persons attending congresses, conventions, seminars, summits, or other meetings. · Diplomatic: interpreting performed to facilitate communication between governments or international organizations or both. · Disaster Relief and Humanitarian: interpreting performed in support of humanitarian operations and individuals affected by disaster or other emergency situations. · Educational: interpreting in settings in which educational services are provided. · Healthcare: interpreting in settings in which medical services are provided. · Labor Relations: interpreting performed for negotiations between management and their workers and unions and their members. · Legal: interpreting in settings in which proceedings related to the administration of justice are performed. Legal interpreting is divided into court interpreting and out-of-court interpreting. · Court or Judicial: interpreting in the courtroom. Depositions fall into this category because testimony is given under oath and afforded the same weight as testimony given in the courtroom. · Out-of-court or Quasi-Judicial: interpreting of interviews and hearings in settings that may have a bearing on legal proceedings. These proceedings include, but are not limited to, interpreting for attorney- client interviews, criminal justice or law enforcement agencies, administrative agencies, as well as boards, commissions, or licensing bodies. Quasi- judicial proceedings affect fundamental individual rights and may give rise to an appeal at the state or federal levels. For this reason, the interpretation of out-of-court hearings and interviews shall be of the same quality and accuracy as that rendered in court. · Liaison: interpreting generally performed in the consecutive mode while escorting visiting individuals or groups. · Media: interpreting performed for media outlets such as television networks, radio stations, or the internet. · Military and Conflict Zone: interpreting performed in support of the armed forces and their mission and individuals affected by armed conflict. · Security Related: interpreting performed in support of government agencies working in law enforcement and national security. · Social Services: interpreting in settings in which human services programs are provided. |

||||||

| Language Pairs and Directions | Spanish <> English (bidirectional)

English > Spanish (e.g. for a presentation) |

||||||

| Dialect(s) | Only if applicable. e.g. Spanish (Iberic) or Arabic (Levantine). | ||||||

| Event’s Setting

(choose only one) |

o One-on-one meeting

o Group meeting o Hearing o Presentation o Conference o Trial o Media o Depositions |

||||||

| Event’s Venue

(choose only one) |

o Conference center

o Meeting room o Courtroom o Correctional facility o Police stations o Detention centers o Educational facility o Office o Theater o Television/radio studio o Healthcare facility o Business/industrial complex o Agricultural/outdoors |

||||||

| The event’s setting and venue will determine the delivery modality, mode of interpreting, number of interpreters, type of interpreter credentials, equipment, attire, security clearance, and immunizations. | |||||||

| Delivery Modality

(choose only one) |

Interpreters are more effective when they have as much information as the other participants in the encounter. This includes facial expressions, gestures, and other visual cues.

o In-person interpreting: provided by interpreters present in the same physical location as the speakers or the audience or both. o On-site: provided by interpreters present in the same physical location as either the speaker AND the audience. o Tele-interpreting: provided by interpreters present in the same physical location as EITHER the speaker or the audience. o Videoconference: provided by interpreters having a video-mediated view of the speakers or the audience. o Audio conference: provided by interpreters having an audio feed (e.g. telephone) of the speakers or the audience. o Remote interpreting: provided by interpreters not present in the same physical location as the speakers and the audience. o Video Remote Interpreting (VRI): provided by interpreters having a video-mediated view of both the speakers and the audience. o Pre-scheduled VRI: provided by interpreters at a previously arranged date and time. o On-demand VRI: provided by interpreters on call. o Telephonic or Over-the-Phone Interpreting (OPI): provided by interpreters having an audio feed (e.g. telephone) of the speakers and the audience. o Pre-scheduled OPI: provided by interpreters at a previously arranged date and time. o On-demand OPI: provided by interpreters on call. o Remote Simultaneous Interpreting (RSI): provided by a team of interpreters through a video conference platform. |

||||||

| Mode(s) of Interpreting

(choose all that apply) |

o Consecutive Interpreting: the rendering of a speaker’s or signer’s message into another language when the speaker or signer pauses to allow interpretation.

o Simultaneous Interpreting: the rendering of a speaker’s or signer’s message into another language while the speaker or signer continues to speak or sign. This mode frequently requires either mobile wireless equipment or booths. o Sight Translation: the rendering of a written document directly into a spoken or signed language, not for purposes of producing a written document. |

||||||

| Number of interpreters needed

(based on duration of interpreting appointment and delivery modality) |

In-person interpreting:

o Consecutive mode To ensure interpreting quality and accuracy, it is recommended that two interpreters be hired for meetings longer than 2 h or dealing with complex, technical, and/or specialized subjects. For meetings lasting up to 2 h or dealing with general, nontechnical subjects, one interpreter may suffice. If the decision is made to retain only one interpreter for a consecutive assignment, the interpreter will be given periodic breaks at his/her discretion. The number and length of breaks may increase in accordance with the complexity of the subject at hand and the length of the meeting. o Simultaneous mode Two interpreters shall be assigned per language for any event lasting over 1 hour. An additional interpreter may be assigned when the team is required to interpret bi-directionally. Given the intensive cognitive activity involved in simultaneous interpreting, interpreters should alternate every 15 to 30 min as deemed necessary by team members. This mode frequently requires either mobile wireless equipment or booths. In remote interpreting, studies have shown that interpreter quality decreases twice as fast, so interpreters need more frequent relief by a team member or more frequent breaks than in in-person interpreting. |

||||||

| Interpreter Specific Requirements

(only when applicable) |

Credentials: Pursuant to federal and state regulations, certain assignments may require specific credential.

Simultaneous interpreting: only WA Court Certified interpreters and DSHS Social Services Level 2 Certified interpreters have had their simultaneous interpreting skills tested scoring above 70%. WA Court Certified or Registered interpreters for Legal and Security Related interpreting. WA DSHS Social Services Certified or Authorized interpreters for Community and Social Services interpreting. WA DSHS Medical Certified or Authorized interpreters for Healthcare interpreting. |

||||||

| Security Clearance: Certain assignments may require different levels of security clearance. | |||||||

| Immunization: Some interpreting assignments may require proof of health screening and immunization for all employees and independent contractors working at certain facilities. | |||||||

| Appropriate attire: The setting will dictate the type of appropriate attire. | |||||||

| HIPAA: certification | |||||||

| Criminal Background Check: WSP or Fingerprints | |||||||

| Background or supporting documents

(only if applicable)

|

To ensure interpreting quality and accuracy, interpreters shall have access to or be briefed on pertinent materials that will be discussed or referenced at the event., such as program/agenda, translated handouts, written text of speeches, handouts, etc., PowerPoint slides, materials from previous meetings, jury instructions, etc. | ||||||

| Working Conditions | Acoustics | When the speakers use microphones, the interpreter is able to hear them more clearly. The interpreter should also have a hands free microphone and a podium for consecutive interpreting. | |||||

| Visibility | The interpreter should have as much visual input as possible including an unencumbered view of the speaker or, in the case of videoconferencing, large screens showing the speaker. Sign language interpreting is particularly dependent upon a clear line of sight between the interpreter and the deaf consumer. | ||||||

| E

Q U I P M E N T |

Booths | Headphone(s) | The interpreter should only hear the speaker, not the interpreter, through the headphones.

Interpreter operated volume control |

||||

| Microphone(s) | Interpreter controlled on/off switch and cough button | ||||||

| Silent ventilation | |||||||

| Soundproof | |||||||

| Writing table: with adequate reading light | |||||||

| Wireless equipment | Transmitters: one per language | ||||||

| Receivers: one per person | |||||||

| Microphones: one per interpreter | |||||||

| Headphone: one per person | |||||||

| On stage Equipment | Microphones: separate hands free microphone for interpreter | ||||||

| Podium: extra podium for the interpreter | |||||||

| Tech support | Contact information for technical personnel for booth, on stage or wireless equipment for setting up, dismantling, and monitoring. | ||||||

| Compensation | Hourly rate: | Minimum duration: | |||||

| No Show: | |||||||

| Late Cancellation: | |||||||

| Transportation | Mileage: | ||||||

| Travel Time Fee: | |||||||

| Parking, ferry, tolls: | |||||||

| Other: | |||||||

| Payment Terms | Timeline for payment: | ||||||

| Mode of payment: EFT, check, credit card, PayPal, etc. | |||||||